|

The Korean text of this paper can be translated into multiple languages on the website of http://jksee.or.kr through Google Translator.

AbstractObjectivesCigarette smoking is an important factor in human exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Machine-smoking methods have been devised to evaluate inhalation exposure to mainstream cigarette smoke. However, there have been only a few studies that have employed these methods for PAH monitoring in Korea.

MethodsTotal particulate matter samples were collected from the mainstream smoke of five different cigarette types using the ISO 3308 standard smoking method. The samples were analyzed for 16 PAHs using a gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (GC/MS) following extraction and clean-up procedures.

Results and DiscussionThe 16 PAH levels of cigarette samples ranged from 87.1 ng/cig to 247.4 ng/cig with an average of 135.4 ng/cig. The average fractions of PAHs classified by the number of rings were as follows: 15% (2 rings), 37% (3 rings), 43% (4 rings), 4% (5 rings), and 1% (6 rings). Diagnostic ratios suggested that the characteristics of PAH pollution in mainstream cigarette smoke were similar to those of biomass burning but different from those of ambient air. The carcinogenic risks of PAHs exceeded the risk threshold of the US EPA (1.0E-06) for the 10%, 30%, and 20% exposure groups of adult males, adult females, and all adults, respectively.

ConclusionThis study highlights the significance of mainstream cigarette smoke in examining human inhalation exposure to PAHs and carcinogenic risks, which are primarily influenced by cigarette smoking rather than ambient air. These findings can contribute to a comprehensive assessment of inhalation exposure to PAHs and provide guidance for the development of environmental health policies aimed at reducing such exposure.

요약목적흡연은 다환방향족탄화수소(PAHs) 인체노출에 기여하는 중요한 요인이다. 국제표준화기구(ISO) 등에서는 담배 주류연의 흡입노출을 평가하기 위해 흡연분석법을 마련하였으나, 국내에서 이 방법을 이용한 주류연 PAHs 모니터링 연구는 매우 부족하다.

방법본 연구에서는 ISO 3308 표준 흡연법에 따른 흡연 변수를 적용하고 자동흡연기를 사용하여 5종 담배 주류연의 총 입자상물질을 채취하였다. 시료추출과 정제 후에 기체크로마토그래프/질량분석기로 16종 PAHs를 분석하였다.

결과 및 토의담배 주류연의 16종 PAHs 함량 범위는 87.1~247.4 ng/cig, 평균 함량은 135.4 ng/cig이었다. 벤젠고리 개수에 따른 PAHs 평균 비율은 15% (벤젠고리 2개), 37% (벤젠고리 3개), 43% (벤젠고리 4개), 4% (벤젠고리 5개), 1% (벤젠고리 6개)였다. 진단비 산정 결과, 담배 주류연 시료는 생체 연소의 영향을 받았으며 일반 환경대기와 오염 기원이 달랐다. PAHs 흡입발암위해도는 성인 남성의 10% 노출군, 성인 여성의 30% 노출군, 성인 남녀의 20% 노출군부터 미국 환경보호청의 기준 허용위해도(1.0E-06)를 초과하였다.

1. 서 론다환방향족탄화수소(Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: PAHs)는 벤젠고리가 두 개 이상인 유기화합물로서 화석연료나 유기물의 불완전 연소 시 부산물로 발생한다[1]. PAHs는 산업 시설[2], 자동차[3], 컴퓨터[4], 건축자재[5], 담배[6] 등의 인위적 요인과 화산활동[7], 산불[8] 등의 자연적 요인으로 대기 중으로 배출된다. 다양한 오염원에서 배출된 PAHs는 대기와 토양을 비롯한 여러 환경 매체에 분포하며[9], 발암성과 돌연변이 유발성을 가지기 때문에 인체노출 시 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다[10]. 이에 따라 환경부에서 PAHs를 유해대기오염물질, 특정수질유해물질, 토양오염물질 등으로 지정하였다.

PAHs의 인체노출량을 파악하기 위해 대기, 수질, 토양, 퇴적물, 식품 등 다양한 매체의 흡입(inhalation), 섭취(ingestion), 피부흡수(dermal absorption) 노출에 관한 연구가 수행되었으나[11], 담배 연기의 PAHs 함량과 인체노출 수준에 관한 연구는 부족한 실정이다. 담배 연기는 흡연자가 입 안으로 흡입하는 주류연과 연소 중인 담배 말단에서 발생하는 부류연이 있으며, 주류연은 흡연자의 직접적인 흡입 위해성과 직결되므로 중요한 노출원이다. 담배 주류연은 수분, 니코틴, 타르(Tobacco Aerosol Residue: TAR)로 구성된다. 타르는 니코틴 제외 건조입자상물질(Nicotine-Free Dry Particulate Matter: NFDPM)로도 불리며 케톤류, 알코올류, 페놀류, 아민류, PAHs를 포함한 탄화수소류, 에테르류, 금속류 등 다양한 오염물질을 포함한다[12].

담배 주류연 중 PAHs의 인체노출량 평가를 위해서는 흡연 습관에 따른 흡입계수를 고려해야 한다. 예를 들어, 한 번에 흡입하는 연기량, 담배 연기 노출면적, 흡입빈도, 흡연시간 등을 흡입노출량 평가에 고려해야 한다. 이에 따라 국제표준화기구(International Organization for Standardization: ISO)와 캐나다 연방보건부(Health Canada)에서 국제공인분석법을 마련하였고, 주로 해외에서 주류연에 포함된 오염물질 모니터링 연구가 많이 진행되었다[6,12-15]. 또한, 흡연법에 따른 다양한 오염물질 농도를 비교하였고[16,17], 발암 및 비발암 위해성을 평가하였으며[18], 실내 흡연으로 발생한 먼지의 PAHs와 중금속을 모니터링하였고[19,20], 2차 흡연[21]과 3차 흡연 노출[22]을 연구하였다. 그러나 국내에서는 다음 사례와 같이 일부 연구만 수행되었다. 담배 흡연기를 이용하여 주류연을 발생시킨 후 입자상 중금속[23,24]과 입자상 및 기체상 PAHs [25]를 측정하였다. 식품의약품안전처는 국제공인분석법에 따른 담배 주류연의 45개 성분 분석법을 제시하였고[26], 유해성분(Harmful and Potentially Harmful Constituents: HPHCs) 모니터링[27]을 수행하였다. 그러나 이 연구에서는 다양한 PAHs 중에서 benzo(a)pyrene (BaP)만 측정했으므로 PAHs의 배출 특성과 위해도를 종합적으로 파악할 필요가 있다.

본 연구에서는 담배 5종의 주류연을 ISO 표준 흡연법에 따라 포집하여 16종 PAHs를 분석하였다. 또한, 진단비(diagnostic ratio)를 이용하여 주류연과 대기 PAHs의 오염 기원을 구분하였고, 위해성평가를 수행하여 주류연에 함유된 PAHs의 발암위해도를 산정하였다.

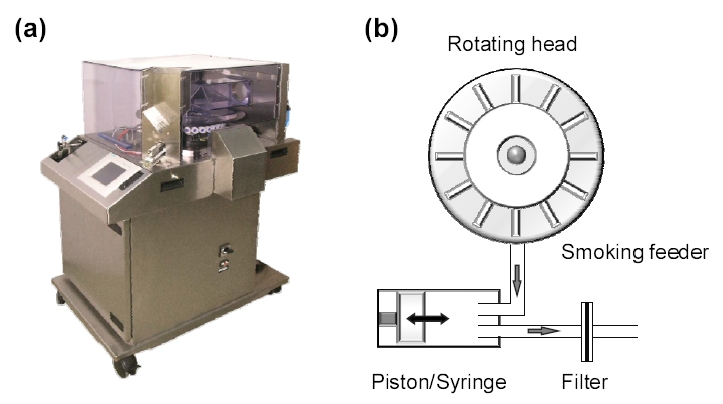

2. 재료 및 방법2.1. 시료채취국내 편의점에서 주로 판매되는 담배 5종(A, B, C, D, E)을 구매하였다. 본 연구에서 사용한 담배 시료의 생산국, 타르와 니코틴의 함량, 담배 형태를 Table 1에 나타내었다. 타르와 니코틴 함량은 담배 제품에 표기된 값을 사용하였다. 담배 주류연의 시료채취는 ISO 3308 표준 흡연법에 따라 천공을 막지 않고(환기차단 0%) 35 mL/회의 흡연부피, 1회/분의 흡연빈도, 2초의 흡연시간을 적용하여 진행하였다[28]. 안전성평가연구소의 담배흡연기(cigarette smoking machine: JB2080, CH Technologies, USA)를 사용하여 기기의 회전 원반(rotating head)에 장착된 담배 거치대(cigarette holder)에 동일 제품의 담배 시료를 일곱 개비씩 거치하고, ISO 4387의 총 입자상물질(Total Particulate Matter: TPM) 측정법에 따라 44 mm 유리섬유필터(Cambridge filter pads, Whatman, UK)에 담배 제품 별로 주류연 TPM을 총 5회 채취하였다(Fig. 1) [29]. 담배 제품 별 시료채취 전에 담배 거치대와 연결 튜브를 세척하고 실내 공기를 환기하였다.

2.2. 시료분석시료별로 분석대상물질의 회수율을 확인하기 위해 대체표준물질(surrogate standard) 5종(Naphthalene-d8, Acenaphthene-d10, Phenanthrene-d10, Chrysene-d12, Perylene-d12)을 유리섬유필터 시료에 주입한 후, 섬유소 원통형 추출여과지(cellulose thimble filter)에 넣고 속실렛(Soxhlet)으로 헥산과 아세톤의 혼합용매(9:1, v/v)를 사용하여 20시간 동안 추출하였다. 추출 시료를 TurboVap (Classic II, Biotage, USA)으로 농축하고, 정제용 유리 컬럼에 활성(130℃, 4시간) 실리카겔 5 g과 무수황산나트륨 4 g을 헥산으로 습식 충진하였다. 농축 시료를 충진된 컬럼에 주입하고 헥산 20 mL를 용출한 후, 헥산과 디클로로메탄 혼합용매(9:1, v/v) 70 mL를 용리액으로 받아 TurboVap과 질소농축기(MG2200, Eyela, Japan)를 이용하여 1 mL로 농축하였다. 최종 시료에 내부표준물질(internal standard) 1종(p-Terphenyl-d14) 50 ng을 주입한 후, 기체크로마토그래프/질량분석기(Gas Chromatograph/Mass Spectrometer: GC/MS, 7890A/5975C, Agilent Technologies, USA)로 분석하였다. GC 컬럼으로는 DB-5MS 모세관 컬럼(30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies, USA)을 사용하였고, 이동기체는 고순도 헬륨이었으며 1 mL/min 유속을 유지하였다. 최종 시료 1 μL를 비분할 주입(splitless) 방법으로 GC에 주입하였다. GC 오븐 조건은 60℃에서 1분간 유지, 26분 동안 10℃/min 속도로 승온, 320℃에서 5분간 유지였으며, 주입구(injector) 온도는 280℃, 이온소스(ion source) 온도는 230℃였다. 70 eV의 이온충격(Electron Ionization: EI)으로 분석대상물질을 이온화하였고, 선택이온 모니터링(Selective Ion Monitoring: SIM) 방법으로 검출하였다. 분석대상물질은 미국 환경보호청(United States Environmental Protection Agency: US EPA)에서 우선관리 대상물질로 지정한 Naphthalene (Nap), Acenaphthylene (Acy), Acenaphthene (Ace), Fluorene (Flu), Phenanthrene (Phe), Anthracene (Ant), Pyrene (Pyr), Fluoranthene (Flt), Benz(a)anthracene (BaA), Chrysene (Chr), Benzo(b)fluoranthene (BbF), Benzo(k)fluoranthene (BkF), BaP, Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene (DahA), Indeno-(1,2,3-cd)pyrene (IcdP), Benzo(g,h,i)perylene (BghiP) 16종 PAHs였다. 담배 제품별 PAHs 분석결과(ng)를 담배흡연기에 장착한 일곱 개비로 나누어 담배 한 개비당 주류연으로 배출된 PAHs 함량(ng/cig)으로 환산하였다.

2.3. 정도관리기기검출한계(Instrumental Detection Limit: IDL)를 산정하기 위하여 저농도 표준용액(0.01 ng/μL)을 7회 반복분석한 값의 표준편차에 99% 신뢰도에서의 t 분포값(3.14)을 곱하였다. 방법검출한계(Method Detection Limit: MDL)를 산정하기 위하여 7개 공시료(유리섬유필터)에 표준물질을 주입하여 실제 시료와 같은 과정으로 전처리하고 분석하였다. 실제 시료의 실험 과정과 동일하게 담배 일곱 개비를 사용한 것으로 가정하고, PAHs 함량 단위(ng/cig)로 환산한 값의 표준편차에 3.14를 곱하여 IDL과 MDL을 산정하였다. 16종 개별 PAHs의 IDL과 MDL은 각각 0.009~0.14 ng/cig과 0.02~0.37 ng/cig이었다. 대체표준물질의 회수율은 Naphthalene-d8 48~60%, Acenaphthene-d10 49~60%, Phenanthrene-d10 66~75%, Chrysene-d12 94~106%, Perylene-d12 95~121%이었으며, 물질별 농도를 회수율로 보정하였다. 시료채취와 실험과정에 발생 가능한 오염을 확인을 위하여 현장바탕시료를 분석하여 시료와 동일한 방법으로 PAHs 함량 단위(ng/cig)로 환산하여 실제 시료의 농도 보정에 사용하였다. 현장바탕시료의 농도는 Nap, Phe, Flt, Pyr이 0.022~0.027 ng/cig 범위였고, Acy, Ace, Fly, Ant, BaA, Chr, BbF, BaP, IcdP, BghiP가 0.001~0.008 ng/cig 수준이었으며, BkF와 DbahA는 불검출되었다.

2.4. 발암 위해성평가담배 주류연의 PAHs 발암 위해성평가를 식 (1)과 식 (2)에 따라 실시하였다[18]. US EPA의 방법에 따라 BaP의 흡입발암잠재력(Inhalation Slope Factor: ISF)으로 PAHs의 발암 위해성을 종합평가하였다[10]. 16종 PAHs의 함량에 독성등가계수(Toxic Equivalency Factor: TEF)를 곱하여 물질별 독성등가치(Toxic Equivalency Quantity: TEQ)를 계산하고 이를 합하여 총 독성등가치(Σ TEQ)를 산정하였다. PAHs의 TEF는 Nap, Acy, Ace, Flu, Phe, Flt, Pyr이 0.001, Ant, Chr, BghiP이 0.01, BaA, BbF, BkF, IcdP이 0.1, BaP와 DahA이 1이다[30]. 즉, 개별 PAHs의 독성에 근거하여 모든 물질의 함량을 BaP 환산 함량(BaP equivalent)으로 계산하였다.

ILCR=LADD×ISF (1)

평생초과 발암위해도(Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk: ILCR)는 일일평균 인체노출량(Life Average Daily Dose: LADD)과 ISF를 곱하여 산정한다. SA (Smoking Amount)는 흡연량(cig/day), EF (Exposure Frequency)는 노출빈도(day/year), ED (Exposure Duration)는 노출기간(year), BW (Body Weight)는 체중(kg), AT (Averaging Time)는 기대수명(day)을 의미한다. 노출기간은 기대수명과 흡연시작연령의 차이로 계산하였고, 각 변수의 값과 분포는 Table 2에 나타내었다. 한국인에 적합한 위해성평가를 수행하기 위하여 국민건강영향조사 자료와 국립환경과학원 노출계수 핸드북의 일일 흡연량, 기대수명, 흡연시작연령, 체중 자료를 사용하였다[31,32]. 고노출군과 저노출군의 노출량 차이를 확인하기 위하여 Crystal ball (Oracle 11.1, USA)을 이용한 몬테카를로 시뮬레이션(Monte-Carlo simulation)으로 10,000회 반복하여 확률론적 위해성평가를 실시하였다. US EPA에서는 발암 위해성평가를 위해 단위위해도(unit risk)를 사용하는 방법을 권장하고 있으나[33], 본 연구에서 담배 연기의 흡입노출에 관한 흡연 변수를 고려하고자 ISF를 사용하는 전통적인 방법으로 진행하였다.

담배 주류연과 일반 환경대기의 발암위해도를 비교하기 위하여 환경대기 중 PAHs에 대한 결정론적 위해성평가를 실시하였다. 흡연량(SA)이 아닌 일일 호흡률(Inhalation Ratio: IR)을 사용하여 일반 환경대기의 ILCR과 LADD를 식 (1)과 식 (3)에 따라 계산하였다. 일반 환경대기의 Σ TEQ는 2020년도 전국 유해대기물질측정망[35]에서 측정한 PAHs 농도의 Σ TEQ를 구하여 중간값(0.09 ng TEQ/m3)을 적용하였다. 각 노출계수는 EF가 252 day/year [36,37], ED가 63.7 year, BW가 64.5 kg, AT가 30,206 day, IR이 14.61 m3/day [32]로 성인 전체 평균값을 사용하였다.

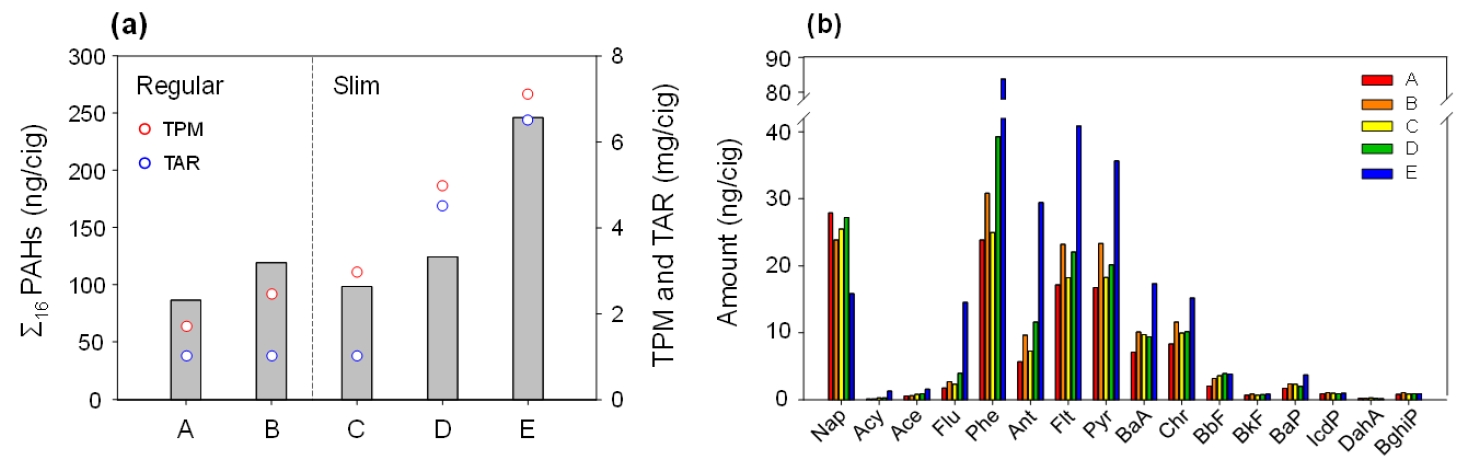

3. 결과 및 고찰3.1. PAHs 함량담배 주류연 시료의 Σ16 PAHs, TPM, 타르 함량을 Fig. 2a에 나타내었다. PAHs 함량은 E (247.4 ng/cig), D (125.4 ng/cig), B (120.2 ng/cig), C (99.5 ng/cig), A (87.1 ng/cig) 시료 순이었고, TPM 함량은 E (7.1 mg/cig), D (5.0 mg/cig), C (3.0 mg/cig), B (2.4 mg/cig), A (1.7 mg/cig) 순서였다. 제품에 표기된 타르 함량은 E (6.5 mg/cig) > D (4.5 mg/cig) > A = B = C (1 mg/cig) 순이었다(Table 1). 전반적으로 Σ16 PAHs 함량은 TPM과 타르에 비례하여 증가하였으며, 세 항목 모두 서로 양의 상관성을 보였다(Spearman correlation, p < 0.05). 그러나 타르 함량이 가장 적은 A, B, C 시료만 고려하면, 시료별로 TPM과 PAHs 함량도 비슷한 수준이라서 세 항목 간에 뚜렷한 상관성을 찾을 수 없었다. 또한, 담배의 형태(일반형과 슬림형)별로 검토한 결과, 슬림형 담배 주류연의 PAHs, TPM, 타르 함량이 평균적으로 많았지만, 통계적으로는 유의하지 않았다(t-test, p > 0.05). 선행연구에서도 담배의 타르 함량이 높을수록 주류연의 PAHs 함량이 높으며[13,38], 타르 함량과 주류연 입자상 PAHs 함량이 양의 상관관계를 나타냈다[38]. 본 연구에서 검토한 담배 제품과 시료 개수가 제한적이므로 일반화하기는 어렵지만, 담배 형태와는 관련 없이 타르 함량이 주류연의 PAHs 함량을 결정할 가능성이 높다.

주류연 모든 시료에서 16종 PAHs가 검출되었다(Fig. 2b). 선행연구에서 작물의 잔여물(잎과 줄기)과 목재 등의 식물 연소 시(300~500℃) 16종 PAHs는 모두 검출되었다[39,40]. ISO 방법으로 담배를 태우면 담배 표면에서 내부까지 온도가 300~700℃로 분포하므로[41], 주류연 시료에서 PAHs 분석대상물질이 모두 검출될 수 있다. 주류연 E 시료는 Nap을 제외하고 저분자량 물질(벤젠고리 3개 이하)과 중분자량 물질(벤젠고리 4개)의 함량이 다른 시료에 비하여 많았다. 시료 전반적으로 Nap (평균 24.1 ng/cig), Phe (평균 40.5 ng/cig), Flt (평균 24.3 ng/cig), Pyr (평균 22.8 ng/cig)의 함량이 많았으며, 이 네 물질이 Σ16 PAHs 함량의 총 69%(각각 15%, 25%, 15%, 14%)를 차지하였다. 한편, 2020년 전국 유해대기물질측정망[35]의 환경대기 중 Σ16 PAHs 농도에 대한 평균 기여율은 Nap 5%, Phe 33%, Flt 16%, Pyr 14%로서 이 네 물질이 67%를 차지하여, 주류연과 환경대기에서 주로 검출되는 물질이 동일하였다.

본 연구와 동일한 ISO 방법으로 시료채취한 선행연구의 주류연 PAHs 함량을 Table 3에 나타내었다. 본 연구의 BaP 함량은 1.7~3.8 ng/cig (평균 2.4 ng/cig)으로, 식품의약품안전처에서 측정한 BaP 함량(1.7~4.5 ng/cig, 평균 2.8 ng/cig)과 비슷한 수준이었다[27]. 해외 선행연구와 비교하면 중분자량과 고분자량 물질의 함량 수준은 비슷하거나[13,14] 다소 낮았다[15,42,43]. 선행연구와 본 연구의 저분자량 물질의 함량은 큰 차이가 났으나[15,42,43] 선행연구의 일부 시료에서는 저분자량 물질 함량이 매우 적었다(Nap: 0.1 ng/cig, Acy: 1.1 ng/cig, Ace: 0.6 ng/cig) [43]. 선행연구의 주류연 Σ16 PAHs 함량 범위가 34.3~1776 ng/cig과[43] 139~2599 ng/cig으로[15] 담배별로 차이가 컸다. 담배 제품별 주류연의 PAHs 함량은 담배의 크기, 형태, 원료, 필터 유형, 제조 공정 등의 영향을 크게 받는 것으로 알려졌다[43,44].

3.2. 진단비 비교본 연구와 선행연구의 담배 주류연, 석유연소(차량, 보일러, 원유 연소), 석탄연소(석탄, 역청탄, 무연탄), 생체연소(화석연소 배출원, 소나무, 참나무, 풀, 볏짚) 시료의 Flt/(Flt+Pyr)과 IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP) 진단비를 Fig. 3a에 나타내었다[45]. 주류연의 두 진단비 범위는 0.50~0.53으로 담배 제품에 따른 차이를 보이지 않았다. 진단비가 0.5보다 크므로 주류연 시료는 생체 연소의 영향을 강하게 받은 것으로 해석할 수 있다. 또한, 일부 선행연구에서 주류연의 IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP) 진단비가 비교적 높은 것을 제외하면, 본 연구의 진단비는 선행연구에 제시된 진단비 수준과 매우 유사하였다[6,43,46]. 선행연구와 비교하여 본 연구에서는 저분자량 물질의 함량이 상대적으로 적었으나, 진단비에 사용되는 중분자량과 고분자량 물질의 비율은 선행연구의 비율과 비슷한 수준이기 때문이다.

주류연 시료의 진단비를 세 종류의 대표적인 PAHs 배출원(석유연소, 화석연소, 생체연소) 시료의 진단비와 비교하였다. 주류연 시료의 평균 진단비(Flt/(Flt+Pyr): 0.51, IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP): 0.52)는 석탄연소(Flt/(Flt+Pyr): 0.55, IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP): 0.54)와 생체연소(Flt/(Flt+Pyr): 0.50, IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP): 0.59) 시료의 평균 진단비와[45] 유사하였다. 이 결과는 담배와 고체연료 연소 과정에서 PAHs가 유사하게 생성되는 것을 의미한다. 반면에 석유연소 시료의 평균 진단비(Flt/(Flt+Pyr): 0.39, IcdP/(IcdP+BghiP): 0.20)는[45] 주류연과 고체연료 연소 시료의 진단비와 큰 차이를 보였다.

흡입노출을 고려하여 주류연과 환경대기(선행연구와 2020년 전국 유해대기물질측정망) 시료의 Ant/(Ant+Phe)과 BaP/BghiP 진단비를 비교하였다(Fig. 3b). 선행연구의 2011년 대산[47], 2011~2012년 울산[2], 2016~2017년 서울[48]의 환경대기 시료의 진단비를 Fig. 3b에 나타내었다. D 시료(타르 함량 4.5 mg/cig)의 Ant/(Ant+Phe)과 BaP/BghiP 진단비(0.23, 2.16)는 타르 함량이 적은(1.0 mg/cig) A, B, C 시료의 진단비와 비슷하거나 낮았으나, 타르 함량이 가장 많은(6.5 mg/cig) E 시료의 Ant/(Ant+Phe)과 BaP/BghiP 진단비는 각각 0.26과 4.05로 다른 시료보다 높아서 연소기원(pyrogenic)과 식생연소 효과가 강하게 나타났다. 모든 주류연 시료의 Ant/(Ant+Phe) 진단비(0.19~0.26)는 0.1보다 높아 석유기원이 아닌 연소기원의 영향을 받은 것으로 진단되었으며, BaP/BghiP 진단비(2.07~4.05)도 0.9보다 높으므로 차량 배출보다 생체연소의 영향을 받은 것으로 평가되었다. 선행연구에서도 주류연 오염특성이 석탄과 생체연소 오염영향과 유사하고 차량 배출 특성과 다르다고 보고하였다[43]. 한편, 선행연구와[2,47,48] 유해대기물질측정망의[35] Ant/(Ant+Phe)과 BaP/BghiP 진단비는 주류연의 진단 비와 크게 차이가 났다. 이 결과는 환경대기와 주류연의 주요 PAHs 물질이 전반적으로 유사하더라도, 진단비를 이용하면 오염 기원을 구분할 수 있다는 것을 의미한다.

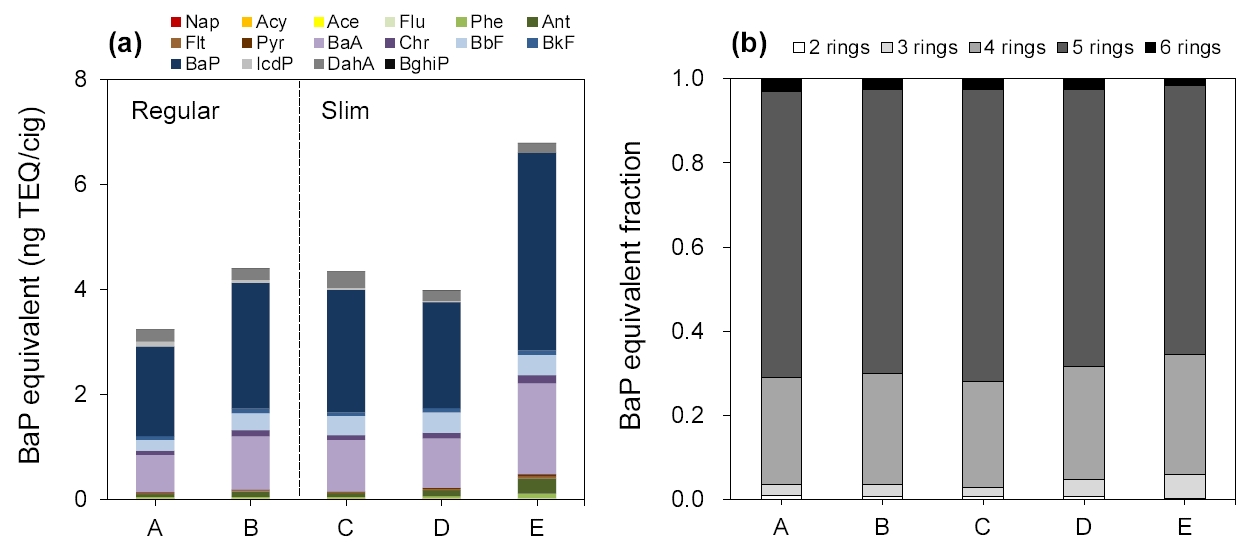

3.3. 인체 위해성평가담배 주류연의 개별 PAHs 함량을 TEQ로 환산하여 시료별로 나타내었다(Fig. 4a). Σ TEQ에 대한 주요 물질별 평균 기여도는 BaP (52.9%), BaA (23.3%), BbF (7.2%), DahA (4.9%), Ant (2.8%), Chr (2.4%) 순이었다. 시료별 Σ TEQ는 E (6.89 ng TEQ/cig), B (4.45 ng TEQ/cig), C (4.41 ng TEQ/cig), D (4.05 ng TEQ/cig), A (3.25 ng TEQ /cig)이었다. 타르 함량이 가장 많은 E 시료는 PAHs 함량과 마찬가지로 Σ TEQ가 다른 시료보다 높았으나, D 시료는 타르 함량이 적은 B와 C 시료보다 Σ TEQ가 낮았다. 이는 비교적 높은 TEF를 갖고 있는 BaA과 BaP 함량이 D (9.4 ng/cig, 2.0 ng/cig)보다 B (10.1 ng/cig, 2.4 ng/cig)와 C (9.7 ng/cig, 2.3 ng/cig) 시료에서 높았기 때문이다.

주류연 시료의 Σ TEQ를 벤젠고리 개수별 구성비로 나타내었다(Fig. 4b). 벤젠고리 개수별 평균 구성비는 벤젠고리 5개(67.0%), 4개(26.4%), 3개(3.5%), 6개(2.4%), 2개(0.6%) 물질 순으로서, 모든 시료가 비슷한 고리 개수 분포를 보였다. 일부 중분자량 물질(Phe, Flt, Pyr)의 함량은 시료별로 차이가 컸지만 TEF가 작으므로(0.001) 이들 물질이 Σ TEQ의 1.9%만 차지했기 때문이다. 이와 유사하게 선행연구에서 보고된 벤젠고리 5개 물질의 Σ TEQ 구성비는 72~82%이었다[15,42,43].

Σ TEQ의 발암 위해성평가 결과(Fig. 5), 성인 남성의 백분위 10% 노출군과 성인 남녀의 백분위 20% 노출군부터 발암위해도(1.039E-06, 1.278E-06)가 US EPA의 기준 허용위해도(1.0E-06)보다 높았고, 성인 여성은 남성에 비해 흡연량이 적고 기대수명이 길기 때문에 백분위 30% 노출군부터 발암위해도(1.109E-06)가 기준치를 초과하였다. 백분위 100% 고노출군의 경우, 발암위해도가 남성(3.203E-05), 남녀(2.629E-05), 여성(1.847E-05) 순으로 높았다. 모든 노출군에서 성인 남성의 발암위해도가 남녀와 여성의 발암위해도보다 높았다. 성인 남녀의 백분위 50% 발암위해도는 2.152E-06으로, 선행연구의 백분위 50% 발암위해도(1.80E-05)보다 8.4배 낮았다[18]. 유해대기물질측정망의 Σ TEQ의 결정론적 발암 위해성평가 결과, 성인 남녀에 대한 발암위해도는 기준치 이하인 4.112E-08로 계산되었다. 이 수치는 본 연구의 성인 남녀의 백분위 50% 발암위해도보다 52.2배 낮았다. 이처럼 흡연자의 PAHs 발암위해도는 일반적인 호흡보다는 흡연을 통해 매우 높아질 수 있다. 물론, 본 연구에서는 시중에 판매되는 일부 담배 시료만을 대상으로 위해도를 산정하였으므로 본 연구 결과를 일반화하기는 어렵다. 그러나 선행연구에서도 주류연의 PAHs 위해도가 기준치를 초과하였다(중간값 1.80E-05) [18]. 또한, 담배 주류연의 기체상 시료에서 저분자량과 중분자량 PAHs가 검출되므로[25,49], 담배 주류연의 실제 발암위해도는 더욱 높을 것이다.

4. 결 론본 연구에서는 담배 5종의 주류연을 ISO 표준 흡연법에 따라 포집하여 16종 PAHs를 분석하였다. 담배 주류연의 PAHs 함량은 TPM과 타르 함량과 양의 상관성을 보였다. PAHs 개별물질 중에서 Phe의 비율이 가장 높았고, 저분자량과 중분자량 PAHs 농도가 총 농도의 대부분을 차지하였다. PAHs 함량은 기존 연구결과 수준과 비슷하거나 다소 낮았고, 저분자량 물질의 함량 차이가 컸다. PAHs 진단비 분석 결과, 주류연의 오염 경향은 화석연소와 생체연소 오염 특성과 유사하였다. 또한, 담배 주류연과 환경대기의 진단비가 크게 달랐다. 고타르 시료를 제외하면 전반적으로 시료들의 Σ TEQ는 비슷한 수준이었으며, 일부 시료의 PAHs 물질별 함량과 Σ TEQ의 경향이 달랐다. 주류연의 흡입발암위해도는 남성 10%, 여성 30%, 남녀 20% 노출군부터 발암 허용위해도를 초과하였다.

본 연구결과는 흡연으로 인한 PAHs의 노출량과 발암위해도가 일반적인 환경대기를 통한 노출량과 발암위해도 보다 상당히 높을 수 있다는 것을 시사한다. 본 연구는 ISO 표준 흡연법에 따른 궐련형 담배 주류연의 PAHs 함량과 위해도를 확인하기 위한 예비연구로 수행되었으므로, 주류연에 함유된 PAHs 이외의 다양한 미량오염물질에 관한 본격적인 모니터링이 필요하다. 또한, 2차 및 3차 간접 흡연을 통한 미량오염물질의 노출을 평가하여 흡연의 종합적인 건강영향을 파악해야 한다. 이러한 연구 결과는 PAHs의 인체 통합 노출평가와 금연보건 정책에 직접적으로 활용될 수 있을 것이다.

NotesDeclaration of Competing Interest The authors declare that they have no known competing interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Fig. 1.Experimental design in this study: (a) cigarette smoking machine (JB2080, CH Technologies, USA) and (b) schematic representation of sampling process.

Fig. 2.Amounts in the individual mainstream cigarette smoke: (a) Σ16 PAHs, TPM, and TAR and (b) each PAH compound.

Fig. 4.BaP equivalents (Σ TEQ) in the mainstream cigarette smoke: (a) TEQs of 16 individual PAHs and (b) TEQ profiles of ring number groups.

Table 1.Detailed information on cigarette products used in this study.

Table 2.Input variables for carcinogenic risk assessment.

Table 3.Comparison of mean PAH amounts (ng/cigarette) in mainstream cigarette smoke measured using the ISO method.

References1. E.-J. Park, H.-O. Kwon, J.-Y. Oh, S.-D. Choi, Levels and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Taehwa river, Ulsan, Korea, J. Korean Soc. Environ. Anal., 15(5), 155-162(2012).

2. T. N. T. Nguyen, H.-O. Kwon, G. Lammel, K.-S. Jung, S.-J. Lee, S.-D. Choi, Spatially high-resolved monitoring and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in an industrial city, J. Hazard Mater., 393, 122409(2020).

3. S.-J. Kim, M.-K. Park, S.-E. Lee, H.-J. Go, B.-C. Cho, Y.-S. Lee, S.-D. Choi, Impact of traffic volumes on levels, patterns, and toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in roadside soils, Environ. Sci. Process Impacts., 21(1), 174-182(2019).

4. S.-H. Seo, K.-S. Jung, M.-K. Park, H.-O. Kwon, S.-D. Choi, Indoor air pollution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons emitted by computers, Build. Environ., 218, 109107(2022).

5. H.-O. Kwon, Y.-S. Lee, J. Ye, H.-S. Son, C.-S. Kim, S.-D. Choi, Levels of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) in a new library, J. Korean Soc. Environ. Anal., 15(1), 1-8(2012).

6. K. Rustemeier, R. Stabbert, H.-J. Haussmann, E. Roemer, E. L. Carmines, Evaluation of the potential effects of ingredients added to cigarettes. part 2: chemical composition of mainstream smoke, Food Chem. Toxicol., 40, 93-104(2002).

7. M. Stracquadanio, E. Dinelli, C. Trombini, Role of volcanic dust in the atmospheric transport and deposition of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and mercury, J. Environ. Monit., 5(6), 984-988(2003).

8. S.-D. Choi, Time trends in the levels and patterns of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in pine bark, litter, and soil after a forest fire, Sci. Total Environ., 470-471, 1441-1449(2014).

9. F.-L. Xu, N. Qin, Y. Zhu, W. He, X.-Z. Kong, M. T. Barbou r, Q.-S. He, Y. Wang, H.-L. Ou-Yang, S. Tao, Multimedia fate modeling of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Lake Small Baiyangdian, Northern China, Ecol. Model., 252, 246-257(2013).

10. US EPA, Development of a Relative Potency Factor (RPF) Approach for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Mixtures, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 1-622(2010).

11. O. C. Ifegwu, C. Anyakora, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: part I. exposure, Advan. Clin. Chem., 72, 277-304(2015).

12. M. Borgerding, H. Klus, Analysis of complex mixtures - cigarette smoke, Exp. Toxicol. Pathol., 57, 43-73(2005).

13. W. Guthery, M. J.. Taylor, Quantitative analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) cited by the United States Food and Drug Administration, Contrib. Tob. Res., 25(6), 607-616(2013).

14. T. Ohkubo, Y. Inaba, Y. Hara, S. Uchiyama, N. Kunugita, Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and mutagenicity of mainstream smoke and heavy metals in tobacco filler of cigarettes of a brand in Japan and cigarettes of the same brand imported privately from other Asian countries, Jpn. J. Hyg., 71, 84-90(2016).

15. A. T. Vu, K. M. Taylor, M. R. Holman, Y. S. Ding, B. Hearn, C. H. Watson, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the mainstream smoke of popular U.S. cigarettes, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 28(8), 1616-1626(2015).

16. M. E. Counts, M. J. Morton, S. W. Laffoon, R. H. Cox, P. J. Lipowicz, Smoke composition and predicting relationships for international commercial cigarettes smoked with three machine-smoking conditions, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 41(3), 185-227(2005).

17. A. Eldridge, T. R. Betson, M. V. Gama, K. McAdam, Variation in tobacco and mainstream smoke toxicant yields from selected commercial cigarette products, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 71(3), 409-427(2015).

18. J. Xie, K. M. Marano, C. L. Wilson, H. Liu, H. Gan, F. Xie, Z. S. Naufal, A probabilistic risk assessment approach used to prioritize chemical constituents in mainstream smoke of cigarettes sold in China, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 62(2), 355-362(2012).

19. E. Hoh, R. N. Hunt, P. J. Quintana, J. M. Zakarian, D. A. Chatfield, B. C. Wittry, E. Rodriguez, G. E. Matt, Environmental tobacco smoke as a source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in settled household dust, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46(7), 4174-4183(2012).

20. G. E. Matt, P. J. E. Quintana, E. Hoh, N. G. Dodder, E. M. Mahabee-Gittens, S. Padilla, L. Markman, K. Watanabe, Tobacco smoke is a likely source of lead and cadmium in settled house dust, J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol., 63, 126656(2021).

21. T. Burkhardt, M. Scherer, G. Scherer, N. Pluym, T. Weber, M. Kolossa-Gehring, Time trend of exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons between 1995 and 2019 in Germany - showcases for successful European legislation, Environ. Res., 216(2), 114638(2023).

22. X. Tang, N. Benowitz, L. Gundel, B. Hang, C. M. Havel, E. Hoh, P. Jacob Iii, J. H. Mao, M. Martins-Green, G. E. Matt, P. J. E. Quintana, M. L. Russell, A. Sarker, S. F. Schick, A. M. Snijders, H. Destaillats, Thirdhand exposures to tobacco-specific nitrosamines through inhalation, dust ingestion, dermal uptake, and epidermal chemistry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56(17), 12506-12516(2022).

23. J.-H. Jeong, Quantitative analysis of trace element in environmental tobacco smoke and its effect on indoor air quality, Master's thesis of Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea, pp. 1-58(2008).

24. J.-M. Lim, J.-H. Lee, Indoor air quality pollution of PM2.5 and associated trace elements affected by environmental tobacco smoke, J. Korean Soc. Environ. Eng., 36(5), 317-324(2014).

25. J.-G. Park, H.-O. Kwon, K.-S. Jung, S.-D. Choi, Monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from mainstream smoke of cigarette, in Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of Korean Society of Environmental Analysis, KS·EA, Ramada plaza, Jeju, pp. 11(2012).

26. MFDS, Analytical Methods of Mainstream Cigarette SmokeCheongju, Korea, pp. 1-231(2018).

27. MFDS, Harmful and Potentially Harmful Constituents (HPHCs) in Cigarette and e-Cigarette ProductsCheongju, Korea, pp. 1-13(2018).

28. ISO, Standard 3308: Routine Analytical Cigarette-Smoking Machine - Definitions and Standard ConditionsGeneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-25(2012).

29. ISO, Standard 4387: Cigarettes - Determination of Total and Nicotine-Free Dry Particulate Matter Using a Routine Analytical Smoking MachineGeneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-19(2019).

30. I. C. T. Nisbet, P. K. Lagoy, Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 16, 290-300(1992).

31. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Home Page, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey raw data, https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do, (2021)

32. NIER, Korean Exposure Factors Handbook, Incheon, Korea, pp. 1-254(2019).

33. US EPA, Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Volume I - Human Health Evaluation Manual Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Inhalation Risk AssessmentWashington, DC, USA, pp. 1-68(2009).

34. CalEPA, Technical Support Document for Cancer Potency Factors: Methodologies for Derivation, Listing of Available Values, and Adjustments to Allow for Early Life Stage ExposuresCalifornia, USA, pp. 1-88(2009).

35. MOE, Annual Report of Air Quality 2020, Sejong, Korea, pp. 1-416(2021).

36. S. C. Chen, C. M. Liao, Health risk assessment on human exposed to environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons pollution sources, Sci. Total Environ., 366(1), 112-123(2006).

37. S.-J. Lee, S.-J. Kim, M.-K. Park, I.-G. Cho, H.-Y. Lee, S.-D. Choi, Contamination characteristics of hazardous air pollutants in particulate matter in the atmosphere of Ulsan, J. Korean Soc. Environ. Anal., 21(4), 281-291(2018).

38. M. Kalaitzoglou, C. Samara, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkanes in the mainstream cigarette smoke of commercial cigarette brands, Fresenius Environ. Bull., 15(8), 738-746(2006).

39. W. Du, X. Yun, Y. Chen, Q. Zhong, W. Wang, L. Wang, M. Qi, G. Shen, S. Tao, PAHs emissions from residential biomass burning in real-world cooking stoves in rural China, Environ. Pollut., 267, 115592(2020).

40. H. Zhang, X. Zhang, Y. Wang, P. Bai, K. Hayakawa, L. Zhang, N. Tang, Characteristics and influencing factors of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons emitted from open burning and stove burning of biomass: a brief review, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health., 19(7), 3944(2022).

41. B. Li, L. Zhao, C. Yu, C. Liu, Y. Jing, H. Pang, B. Wang, K. G. McAdam, Effect of machine smoking intensity and filter ventilation level on gas-phase temperature distribution inside a burning cigarette, Contrib. Tob. Res., 26(4), 191-203(2015).

42. Y. S. Ding, X. J. Yan, R. B. Jain, E. Lopp, A. Tavakoli, G. M. Polzin, S. B. Stanfill, D. L. Ashley, C. H. Watson, Determination of 14 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream smoke from U.S. brand and non-U.S. brand cigarettes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 1133-1138(2006).

43. B. Gao, X. Du, X. Wang, J. Tang, X. Ding, Y. Zhang, X. Bi, G. Zhang, Parent, alkylated, and sulfur/oxygen-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream smoke from 13 brands of Chinese cigarettes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49(15), 9012-9019(2015).

44. Y. S. Ding, J. S. Trommel, X. J. Yan, D. Ashley, C. H. Watson, Determination of 14 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream smoke from domestic cigarettes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39(2), 471-478(2005).

45. R. J. Sheesley, A. Andersson, Ö. Gustafsson, Source characterization of organic aerosols using Monte Carlo source apportionment of PAHs at two South Asian receptor sites, Atmos. Env., 45(23), 3874-3881(2011).

46. D. Moir, W. S. Rickert, G. Levasseur, Y. Larose, R. Maertens, P. White, S. Desjardins, A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 21, 494-502(2008).

47. P. Q. Thang, S.-J. Kim, S.-J. Lee, J. Ye, Y.-K. Seo, S.-O. Baek, S.-D. Choi, Seasonal characteristics of particulate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a petrochemical and oil refinery industrial area on the west coast of South Korea, Atmos. Env., 198, 398-406(2019).

48. P. Q. Thang, S.-J. Kim, S.-J. Lee, C. H. Kim, H.-J. Lim, S.-B. Lee, J. Y. Kim, Q. T. Vuong, S.-D. Choi, Monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using passive air samplers in Seoul, South Korea: spatial distribution, seasonal variation, and source identification, Atmos. Env., 229, 117460(2020).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||